Equine Massage

LESSON SEVEN

PART

TWO

I. AREA BETWEEN LAST RIB

1. Peter Goody – diagram 2 (page 13), diagram 4

(page 20)

2. A Coloring Atlas – plates 16 and 17

This one small area has a number of muscles attachments that are very

important for the forward/backward swing of the hind legs, correct bending,

lateral movements in the hind legs and canter departs. The ones that you will be affecting the most

with your massage are:

1. The muscle portion of the Tensor fascia latae

2. Iliacus (under the

Tensor fascia latae)

3. External oblique

4. Internal oblique

5. Transverse abdominis

Improper balance and tightness in this area can prevent the hindquarters

from working correctly. Often, what

appears to be a problem with the working of the hind legs is actually tightness

in this area (or in the loins).

Techniques

The best techniques will be direct pressure with thumb and finger tips,

cross-fiber friction with thumb or braced fingers, and compression with a stiff

rubber curry comb. This whole area is

very important, be sure to work all around the edge of

the point of the hip, the area between the point of hip and the last rib and

along the “ropy” edge of the Iliocostalis. Again, adjust your pressure to the tightness

or soreness of the area.

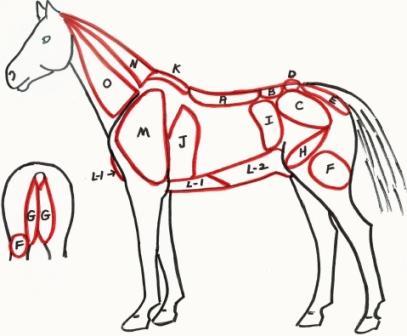

J. AREA BEHIND THE SHOULDER

1. Peter Goody – diagram 3 (page

17) and diagram 4 (page 20)

2. A Coloring Atlas – plates 16,

17, 21

3. Diagrams from lesson 2

This area contains two very important forehand muscles – the thoracic

Serratus and the muscle portion of the Latissimus dorsi.

• THORACIC SERRATUS

The entire Serratus muscle, thoracic and cervical portions (in

conjunction with the pectoral muscles of the chest) is active in lifting the

forehand and arching the horse’s neck.

This muscle is composed of thirteen long slender “fingers” that converge

into a muscle mass on the inside of the shoulder blade, at the top, just under

the Rhomboid attachment. These muscle

“fingers” attach to the lowest four neck vertebrae (cervical 4, 5, 6, and 7) and

the first nine ribs. In our massage we

can access all four of the cervical Serratus and those attaching to ribs 6

through 9. Those attaching to the first

five ribs are under the shoulder blade and not accessible, but your massage of

the others, because of their common origin, will have a positive effect on

these as well.

When this muscle is working correctly, the contraction of its thoracic

“fingers helps lift the front portion of the rib cage and, along with the

abdominals, is a very important component in the process of lifting the horse’s

back.

If the Serratus is not contracting properly, the lower portion of the

chest and neck sink downward and you’ll see a horse that is “on the forehand”

and very possibly “down in the back” and “ewe-necked”.

Soreness in the thoracic Serratus is a common cause of girthing

problems.

The cervical portion of the Serratus lifts the downward curved section

of the neck vertebrae (lower neck).

There will be more about the cervical Serratus in Section O—other neck

muscles.

• LATISSIMUS DORSI

The other important muscle in this area is the belly portion of the Latissimus dorsi. This is a broad, flat, thin muscle. Remember from lesson 2 that the portion that attaches

to the vertebrae of the back is fascia (connective tissue) and the portion that

attaches to the humerus in the lower shoulder is a

tendon. The belly of this muscle

over-lays a portion of the thoracic serratus.

This muscle is an extensor; its job is to stretch, allowing and

supporting the forward swing of the front leg; then it contracts as the leg

swings back. Any tightness, soreness,

spasms, trigger points or adhesions in this muscle will interfere with the full

swing of a front leg.

Techniques

Massage done over the area behind the shoulder will loosen and rebalance

both the thoracic Serratus and the belly of the Latissimus

dorsi.

Notice that the muscle fibers of these two muscles go in different

directions. As you massage, when you’re

going with the fibers of one, you’ll be going across the fibers of the other;

so almost any direction in your massage will be beneficial.

Start with broad strokes of back and forth friction and deep effleurage

over the entire area. Circular motions

and compression are also very effective.

You can usually use a good amount of pressure here unless the area is

very sore. Tools like a small stiff

curry comb or Grooma work well, but the area is too

“fleshy” for muscles combing to be a good choice.

Soreness in this area can come from over-extension of the front legs

(extended trots, jumping), but also from poor saddle fit and girthing

procedures.

K. WITHERS

1. Peter Goody – diagram 4 (page

20)

2. A Coloring Atlas – plate 17

The area over the withers has attachments for two important

muscles. One is the Trapezius

of the superficial layer, which I’ll talk about with the shoulder area. The other muscle, under the Trapezius, is the Rhomboid.

The Rhomboid covers the withers and also stretches up the crest line of

the neck to the poll.

The Rhomboid has two essential functions. First, it attaches the top of the shoulder

blade to the withers. The shoulder blade

hangs suspended from the withers by this muscle, making it the pivot point for

the swing of the shoulder blade.

Its other function, in conjunction with deep ligaments, is to support

the neck along the crest line and facilitate its stretch. Massaging the neck portion of the Rhomboid

will be part of the section dealing with the neck.

At the withers, the Rhomboid is a short, strong muscle; its origin

attaches directly to the bones of the withers (the spinous

processes or ribs 2 – 6). Its insertion

is to the top of shoulder blade, on the inside surface.

Common reasons for soreness in the withers are a saddle that does not

fit correctly or one that has been placed too far forward over the

withers. A saddles that is so wide or

ill-fitting that it touches and puts pressure on the wither bones can lame a

horse, sometimes permanently. The

presence of white hairs on the withers often indicates that there has been, or

is, a saddle problem.

Techniques

The muscle fibers run straight from the withers to the shoulder

blade. You can use techniques that go

with or across the muscle fibers.

Working across the fibers will separate them,

going with the fibers helps them stretch.

Friction works very well in this small area, but compression and muscle

combing are also appropriate. Depending

on whether this muscle is tight or sore, you can use either your finger tips or

curry comb.

One technique that I like involves reaching over the withers and pulling

toward me with finger tips. This would

be using a combination of finger tip compression and rocking.

Another effective rocking technique for the withers has you placing one

hand on the side of the neck just in front of the withers, the other hand

reaches over the withers, hooking fingers into the wither bones. Now, push against the neck and pull the

withers toward you. Set up a rocking

motion by alternating the push and pull.

These rocking techniques also loosen other muscles in the forehand and

base of the neck and will help in balancing the forehand.

L. BELLY LINE

1.

Peter Goody – diagram 3 (page 17), diagram 4 (page 20), diagram 13 (page 45)

2.

If you have “An Atlas of Animal Anatomy for Artist” by Ellenberger, Dittrick and Baum, there is a very good diagram showing a view

of the belly/chest of the horse.

This section deals with massaging the entire underline of the horse, but

I have divided it into chest muscles and abdominal muscles.

(L – 1)

Chest muscles – behind, between and in front of the forelegs

(L – 2)

Groin and abdominal muscles

The major muscles of the belly line, both pectorals and abdominals, are

flexors—their job is to contract.

• L – 1 THE CHEST MUSCLES (pectorals)

Three of the horse’s four pectorals are in this area (the fourth is in

front of the shoulder blade). These

pectorals are flexors that support the rib cage from the bottom and both

stabilize and allow movement of the front legs.

Frequently these muscles, as well as the abdominals, are tight in an

extended state and do not contract properly.

When these pectorals are in that extended state, without good capacity

for contraction, they allow the rib cage to settle downward, preventing them

from doing their part in elevating the forehand for collection. Your job will be to loosen these muscles so

that they can contract and extend correctly.

The three pectorals all have their origin along the edge of the breast

bone (sternum) and all three attach at different places on the humerus. You will

find different names for these pectorals in various anatomy books. For my purpose of describing them for you and

to simplify and avoid confusion, I will talk about them in relationship to the

forelegs. You can choose which of the

anatomical names you wish to use for them.

(I am describing these muscles just on one side of the horse, but you

understand that they occur on both sides.)

There is a pectoral behind the forelegs, one between the forelegs and

one in front of the forelegs.

Massage

Techniques

A.

Pectoral behind the forelegs – this is a fairly long muscle that starts

in the area near the elbow and runs back along the belly line to the end of the

rib cage. The muscles fibers also run in

this direction.

1.

First, with finger tips, use deep pressure where this muscle attaches to the

breast bone (sternum).

2.

Next, with your hand or rubber curry, use deep effleurage or broad (rather than

finger tip) friction over the entire surface of the muscle, going with and across

the fibers.

3. If the muscle is

very tight, do some muscle combing with one of the tools.

B.

Pectoral between the forelegs – this is a short, broad muscle that goes

from the inside of the humerus to the breast

bone. If it is tight, its attachment on

the inside of the elbow can inhibit the forward swing of the humerus. You will

want to pay attention to releasing tension at this point.

1.

Use finger tip deep pressure where this muscles attaches to the breast bone.

2.

Do friction on the inside of the elbow, up along the inside of the humerus and across the muscle between the humerus

and breast bone.

3.

This muscle also goes down into the foreleg, attaching to the radius. Peter Goody’s book shows

this quite well (diagram 13). Do

friction on this attachment.

C.

Pectoral in front of the forelegs – looking at the horse from the front

you’ll see it as a “fleshy” muscle—what we think of as the chest muscle.

1. Use deep finger

tip pressure along the breast bone attachment.

You will be able to feel the front point of the breast

bone—work from that point down to the front legs.

2. Do friction where

this muscle attaches to the humerus.

3. Do kneading in the

fleshy part of the muscles.

Once these muscles have been loosened by

massage, there are some finger pressure techniques that I use to confirm that

the muscles can now contract properly and lift the forehand. These techniques also allow the horse to

become aware of new possibilities in the way its muscles can work.

Techniques for Raising the Chest.

The following maneuvers will raise the horse’s

back behind the withers (under the saddle).

You will be working on the pectoral behind the front legs.

1.

Stand facing the horse’s side. Starting

where the muscle attaches at the

end of the rib cage, put your fingers into the muscle a few inches away from

the breast bone. Use your thumb or

braced fingers to push up into the muscle, then push forward, going toward the

front of the horse. Your pressure needs

to be up as well as forward. You want to

feel like you’re actually pushing the back up; and you want to see the back

rise, even if only a small amount—but you would like to see it rise a lot. If the horse’s back doesn’t give some lift,

do more massage work on these pectorals, especially muscle combing, and try

again.

2.

Now, go to the other side of the horse and reach just across the mid-line of

the belly (your fingers will be on the side you have been working on). Push up into the muscle with your finger tips

and then pull toward you. Repeat this,

moving your fingers forward along the edge of the breast bone from mid-belly to

the front legs. Again, you want to feel

and see the area behind the withers (under the saddle) rise.

3. Repeat this on the other

side.

Technique for Raising the Withers.

For this maneuver you will be working on the pectoral between the front

legs. It requires that you use both

hands. When it is combined with the

techniques for raising the horse’s back behind the

withers, the entire forehand will elevate.

1.

Place one hand at the back edge of this muscle, put

the other at the front of the muscle.

2.

Using thumb pressure, one hand is going to slide into the pectoral, coming from

the back; the other will slide between the legs,

coming from the front.

3.

Press upward into the muscle and then push your thumbs toward each other.

4.

Your thumbs should meet between the front legs with upward pushing pressure.

5.

Push up with both thumbs. This upward

pressure should cause the horse to lift its withers.

You should feel and see the withers rise.

6.

Repeat on the other side.

These chest muscles can be extremely tight on many horses. If these techniques do not lift the forehand,

go back and do more massage work on the muscles.

• L – 2 GROIN

I have left describing massage in the groin and belly muscles until now

because of safety considerations. Many equine

massage routines do not deal with this area at all, but doing so is very

important for bringing all of the parts of the horse together into a working

whole. It cannot be ignored. But it is important for you to know how to

work in this area safely.

When a horse feels a touch in the belly, kicking at that touch is a

common reaction; be prepared for that.

Some horses will just pick up a foot, some will kick up toward their

belly, some will kick out at you. With horses that you do not know, it is safer

to let the horse get accustomed to pressure on its belly line by first working

in the chest area (as well as on the adductors) before going to the abdominals

and groin. But once the horse is

comfortable with pressure in this area, you can do either chest or abdominals

first, depending upon what seems appropriate for the horse’s problem. Whether you work on this area in a first

massage is really a judgment call based on a horse’s degree of soreness, where

the major problem is and the sensitivity level of the horse. If they’re defensive about this area at

first, they will usually let you work there in your second session.

We are dealing with three major muscles in this area – the Internal

oblique, the Rectus abdominis and the lower edge of

the External oblique.

1.

Peter Goody – diagram 3 (page 17) – This shows the attachment of the External oblique to the abdominal fascia

(heave line). Diagram 4 (page 20) shows

a cut-away of the abdominal fascia showing the Internal oblique.

2.

A Coloring Atlas – plates 16 and 17 show the same muscles.

• Internal oblique

The Internal oblique goes from the point of the hip down to the center

of the belly line in the area we call the groin. It is triangular in shape and acts as a

“sling”, supporting the intestines.

• Rectus abdominis

The Rectus abdominis is a strong flexor and is

important for the support of the horse’s back.

I have not seen an equine anatomy book that has a good diagram of the

Rectus abdominis; they all show just the abdominal

fascia that covers the entire abdominal area, with a cut-away showing the

Internal oblique. Diagrams of the human

Rectus abdominis will give a good picture of what

this muscle also looks like on the horse.

It’s composed of two long muscles on either side of the center line of

the belly. They run the length of the

belly from attachments on the rib cage to the front of the pubic bone. In massaging the Rectus abdominis

you will be working through the abdominal fascia. The only portion of the Rectus abdominis we cannot access easily is that which is under

the sheath or teats.

When the Rectus abdominis is working

correctly, the contractions lift the horse’s back and pull the pelvic bone

down. This allows the hind legs to swing

forward under the body, giving them more thrust and power.

• The External oblique

This is a very thin muscle that covers the sides of the horse’s rib

cage. Its lower edge connects to the

abdominal fascia. Tightness along the

lower edge of this muscle inhibits the movement of the rib cage and the

expansion of the lungs. This edge is the

tight line we see in horses that have heaves.

Techniques

The skin in the abdominal area is sensitive, the only place were tools

would be appropriate would be along the lower edge of the External oblique.

I have two positions I use when standing next to a horse to do massage

in the groin. One is to stand close,

next to the hind leg, either facing the horse or facing somewhat forward. I will have one forearm (the right if I’m

working on the left side) lying on the horse’s side just above the stifle. In this way I can exert downward pressure on

the stifle if the horse tries to lift the leg or kick. Sometimes I will stand forward of the stifle,

facing the horse’s belly, so that I can bring a hand into the forward portion

of the belly and work backward. You’re

more exposed to a kick from a hind leg when you’re in this position so it’s

best to wait to use this approach until the horse is comfortable with belly

line work.

Work in the Groin (Internal oblique)

1.

You will have already done work around the stifle when you worked on the

quadriceps, so start by touching the outside of the stifle, then slide your

hand to the inside of the stifle, allowing the back of your hand to touch the

abdomen. This is the horse’s introduction to your touch. The muscle under the fascia here is the Internal oblique. You

will use your finger tips, the heel of your hand or the back of your fist in

your work.

2.

Using with finger tips, you will first do connective tissue massage on the

fascia. Start near the stifle and move

up the groin with a gliding pressure, moving toward the pubic bone area. Remember—this is the techniques where you

want to feel like you’re moving toothpaste around in a tube. Repeat until you feel the area soften a

little.

3.

Now, working in the same area, use more pressure in order to affect the muscle

under the fascia. You can use the heel

of your hand, the fist or heavier finger pressure. When the horse responds to this pressure, you

will feel the area lift slightly.

4.

Next, using the same gliding pressure, start next to the stifle and work

forward toward the rib cage and downward toward the belly line. You can now use heavier pressure—use as much

as the horse allows. I will stand either

with my shoulder against the stifle and work toward the rib cage, or sometimes

I find it easier to stand more toward the shoulder, facing to the rear, and

work from the rib cage toward the stifle.

The choice will really depend on how the horse responds to what you’re

doing.

Work

on the External oblique

1.

Work along the lower edge of this muscle using deep effleurage, compression and

broad stroke friction. Start at the point

of the hip and work toward the elbow.

You can use heavy pressure along this line and a stiff curry comb works

well.

Work

on the Rectus abdominis

1.

Do connective tissue massage first, using finger tip pressure along the length

of the muscle from its rib attachments to the sheath or teats. In a male horse, you can usually work along the sides of the sheath. A mare might allow you to do some pressure

work between the teats.

2.

Next, you will use heavier, upward pressure that will affect the muscle, using

your thumbs, fingers or fist.

3.

The last thing that you will do in this area is ask the horse to lift its back

behind the saddle. (Your work on the

pectorals lifted the back under the saddle.)

You’ll use the same technique as you did for lifting the chest and

withers. Stand on one side of the horse,

reach across the center line of the belly and, with finger tips, push up into

the muscle and pull toward you. You can

use one or both hands to do this. Do

this in a number of places along the belly line. Rocking the torso at the same time can help

the lift.

M. SHOULDER

1. Peter Goody – diagram 3 (page

17), diagram 4 (page 20)

2. A Coloring Atlas – plates 16

and 17

There are five important muscles in the

shoulder area.

1.

Supraspinatus

2.

Infraspinatus

3.

Deltoids

4.

Triceps

5.

the fourth pectoral

1.

SUPRASPINATUS and 2. INFRASPINATUS

These muscles lie on the surface of the shoulder blade, one on either side

of the spine of the shoulder blade and are covered by the Trapezius

and the Deltoid. These are long muscles

that are almost totally attached to the shoulder blade. Their insertion is to the head of the humerus, which is just a short distance away. This means that there is only a small portion

of these muscles that has the capacity for good contraction and extension. Their major job is to support and stabilize

the shoulder joint as it opens and closes.

They are subject to both stress points and trigger points.

Techniques

It is easy to work on these muscles through the Trapezius

and Deltoid. There are a number of

massage techniques that work well here.

Because there is bone behind them, you can separate the muscle fibers by

pushing the muscles against the bone.

Compression and deep effleurage are good techniques for doing this. Friction and muscle combing are also

effective techniques for this area. Work

primarily up and down these muscles, rather than across—go with the muscle

fibers. You can use your hands or

tools. Use deep static pressure on any

small areas of intense soreness such as trigger and stress points.

2.

DELTOID

The Deltoid is part of the superficial layer and over-lays the Infraspinatus. It is

also involved with stabilizing and controlling the opening and closing of the

shoulder joint. Its fibers run in the

same direction as the Supraspinatus and Infraspinatus

Techniques

All of the massage that you do for the Supraspinatus

and Infraspinatus will also be affecting the Deltoid.

4.

TRICEPS

The Triceps is an extensor muscle.

It stretches as the muscles in the chest (flexors) pull the humerus forward. Its

contraction returns the humerus to its normal

anatomical position.

Techniques

The Triceps is a large, fleshy muscle that will respond well to

compression (especially “compress and glide”) and kneading. You can go across the fibers and with the

fibers. You may find small, sore spots

(chunky peanut butter) in the muscle. If

so, use deep, static pressure as for stress and trigger points.

5.

4th PECTORAL

I discussed three of the pectoral muscles under Section L (Chest

Muscles). This fourth pectoral lies just

in front of the shoulder blade and runs in the same direction as the Supraspinatus and Infraspinatus. This is a very strong muscle whose

contraction is important in opening the shoulder joint and pulling the bottom

of the shoulder blade forward. Its

origin is on the breast bone (sternum) along with the other three

pectorals. It wraps around the shoulder

joint and inserts on the top portion of the shoulder blade. In horses that are tight in their shoulders

and lower neck, it will feel like a tight, hard “rope” in front of the shoulder

blade.

Techniques

This is not an easy muscle to massage effectively. The massage that you do on the portion in

front of the shoulder will be preparation for getting this muscle to release,

but you won’t really see result until you release tension in the chest and

lower neck. On the portion in front of

the shoulder blade do compression and friction, going across as well as with

the fibers. The massage that you do

along the breast bone (sternum) for the other pectorals will also loosen this

part of this 4th pectoral.

N. RHOMBOIDS—NECK SECTION

1. Peter Goody – Diagram 4 (page

20)

2. A Coloring Atlas – plate 17

As the horse’s neck arcs out into space, it needs strong support muscles

and ligaments to keep it from being dragged down by the weight of the

head. The Rhomboid is one of the muscles

that do this job.

The part of the Rhomboid muscle across the withers not only forms the

attachment for the top of the shoulder blade, but also forms the attachment for

its neck portion as it stretches all the way up the crest line.

The Rhomboid connection to the shoulder blades as well as to the crest

line of the neck explains why tight, restricted shoulder movement and stiffness

in the crest line seem to go together.

Riders often find that if they can get the shoulders moving, the neck

will loosen and stretch; or, if they can get the neck to stretch, the shoulders

will swing better.

Techniques

The neck portion of the Rhomboid is an easy muscle to massage. It is part of the second muscle layer, but

the superficial muscle that covers it, the Trapezius,

is quite thin.

You can massage across or with the fibers. Friction across the fibers will be very

effective in the portion closest to the withers. When going up the crest line, massage with

the fibers, using deep effleurage, “compress and glide” or broad stroke, back

and forth, friction. A stiff rubber

curry is very effective on this muscle.

Horses usually enjoy this crest line work and you’ll see them stretch

their necks as you go up the muscle.

You may find sore or hard spots as you go. These could be trigger points, scar tissue or

adhesions—often from fights or play with other horses. Deep cross-fiber friction is the best

technique for scar tissue and adhesions; static pressure for trigger points.

This muscle is an extensor and it should stretch fully from its anchor

at the withers, but on some horses you may see a dip just in front of the

withers. This dip indicates a tightness

in the muscle (and the ligaments underneath) at that point that prevents the

complete outward arc and stretch of the neck.

This dip can vary from a slight curve to a deep, sharp dip. The deeper the dip, the more significant is

the constriction.

After a general loosening of the entire Rhomboid, you can use deep

friction with thumb and fingers and muscle combing to do specific work on this

constriction. After this deep work that

separates the muscle fibers, you can finish with some rocking. But you need to know that the massage work is

only part of the solution to this problem.

These muscles and ligament are incredibly strong and do not change

easily. Lifting the chest and back and

teaching the horse to move forward from behind is the only way to get this area

to truly stretch, and this takes time.

Usually, it will take six months to a year before you will see this area

fill in. You will need to be able to

explain this to your client.

TRAPEZIUS

I have not discussed massage for the Trapezius

because it is a thin muscle whose primary job is to hold the shoulder blade

against the rib cage. Problems that

affect the swing of the shoulder blade are almost always going to be in the

deeper level. If there is some

restriction in the Trapezius, it will usually get

worked out as you massage the deeper muscles.

This is true for the thoracic (rib cage) portion of the Trapezius (the part under the saddle) as well as the

cervical (neck) portion.

O. OTHER NECK MUSCLES

1. Peter Goody – diagram 3 (page

16), diagram 4 (page 20)

2. A Coloring Atlas – plates 16

and 17

The three muscles in the rest of the neck (not crest line muscles) on

which I concentrate my massage are:

1.

Brachiocephalicus

2.

Cervical Serratus

3.

Splenius

These are large muscles with

important functions and they are readily accessible for massage.

There are many other muscles in the neck that are important for its

correct functioning, but most are deep and not accessible for direct

massage. As the massage loosens and

rebalances the ones we can access, it will also have a positive effect on the

deeper ones.

1.

BRACHIOCEPHALECUS

All through this course I have stressed the many similarities between

horse and human anatomy and suggested that you try placing and moving your own

body in the same way as a horse in order to experience some of the stresses and

tensions the horse’s body may be feeling.

But I cannot find any muscle in the human body that corresponds to the Brachiocephalicus.

This is a long, fairly wide

muscle that has its origin at the poll, just behind the ear. It goes down the neck vertebrae, passes over

the shoulder joint and inserts on the humerus, about

mid-way between the elbow and the shoulder joint. To hold it in place over this distance, it

has attachments on the 2nd, 3rd and 4th neck

vertebrae and on the shoulder blade.

This muscle is a flexor; when it contracts, it pulls the shoulder and

head closer together and arches the neck.

A horse standing or just moving in natural posture does not give you a

good chance to see this muscle at work.

Horses that are “working through their backs” will show this muscle

contracting as the top line of the neck stretches. Two ways to see this muscle working to its

maximum are to watch horses jumping large fences (particularly in the take-off

phase) and in high collection.

The crest line muscles are the extensor companions to the Brachiocephalicus.

If they are tight and do not lengthen well, it will interfere with the

correct working of the Brachiocephalicus. This muscle also works in concert with the

Serratus to elevate the chest.

Techniques

This is a broad muscle that is readily accessible to massage from its

origin to its insertion. You can use any

number of techniques on it. The best

would be those that push into the muscle and then move up the neck from the

shoulder to the poll. Some of these

could be:

1.

deep effleurage up the entire neck, separating muscle

fibers by pushing the muscle against the neck vertebrae

2.

regular compression and compression of the “press and

glide” type

3.

back and forth friction, working up and down the

muscle, going across the fibers as well

as with the fibers

A stiff curry comb or Grooma type tool works

very well on this muscle, especially when separating muscle fibers by pressing

the muscle against the bones of the neck.

You may feel tight spots in this muscle as you work over the lower neck

vertebrae. This is rarely a problem in

the Brachiocephalicus, but rather it is usually in

the cervical attachments of the Serratus.

If a horse reacts to your work on this muscle with acute sensitivity and

pain there is a good possibility that the neck vertebrae are out of alignment

and a chiropractor needs to look at the horse.

Loosening the neck muscles may sometimes correct minor misalignments,

but if the sensitivity persist suggest that the owner

call a chiropractor.

There is important work to be done at the poll attachments of the Brachiocephalicus, but I’ll discus this with the massage

work on the head, jaw and poll.

CERVICAL SERRATUS MUSCLES

1.

Peter Goody – diagram 4 (page 20)

2.

A Coloring Atlas – plate 17

The cervical portion of the Serratus attaches to the lower four neck

vertebrae (C 4, 5, 6 and 7) and is a very important part of the complex of

muscles that lift the forehand and extend and arch the neck. It does its part by contracting and lifting

the curve in the lower neck vertebrae.

With most muscles, correct function is usually inhibited by the muscle

being overly contracted and too tight.

This is not the case with the Serratus.

When the Serratus “fingers” are not working correctly, they lack tone and

do not contract to lift the lower neck vertebrae and the rib cage. If you see hollow areas in the lower neck,

just in front of the shoulders, you will know that this muscle is slack and

lacks tone; it is not engaging and doing its job.

This muscle is also very important for lateral flexion and bending in

the lower neck.

Review section J (Area Behind the Shoulder) for

a more complete description of this muscle and its function.

SPLENIUS

Neither Peter Goody nor A Coloring Atlas shows a good picture of this

muscle in its entirety. “The Anatomy of

the Horse” by Way and Lee has a very good diagram of this muscle.

The Splenius is a broad muscle whose origin is at the withers. It fans out to fill the space on the side of

the neck above the cervical Serratus. It

attaches to the poll at the occipital bone (behind the ears), to the Atlas (1st

vertebrae) and to the 3rd, 4th and 5th

vertebrae. It is important for both

lateral and longitudinal flexion of the upper portion of the neck and the

head. I will discuss its function in

more detail in the section on the head, but the general massage work that you

do for the neck will loosen the bulk of this muscle.

Techniques

There are three types of massage that you’ll do on the sides of the neck

in the space between the vertebrae and the crest line.

1.

You will do general massage for the entire area. This will cover the Splenius in the upper

portion as well as the Serratus in the lower part. You will be affecting many other muscles, but

these two are large, close to the surface and are major support muscles. You’ll use deep effleurage, circular or back

and forth friction, compression, compress and glide and perhaps some muscle

combing. You can do all of these with

your hands or with tools

I usually start at the base of the neck and

work upward toward the head. This

general work will loosen the muscles and prepare them for both longitudinal and

lateral flexion. This approach would

have you working across the fibers of both the Serratus and Splenius.

2.

The second type of massage you’ll do will be to release constrictions and

possible adhesions where the Serratus and Splenius attach to the neck

vertebrae. This will be particularly

important for the Serratus attachments.

You’ll use direct thumb and finger cross-fiber friction and deep, static

thumb and finger pressure along the top edge of the neck vertebrae where these

muscles attach. You may need to use a

lot of pressure against the vertebrae.

3.

The third is a group of techniques you’ll use for lateral flexion in the base

of the neck. These techniques will be

various types of Positional Release and Rocking. Review these techniques from lesson 6. Do the Positional Release first and finish

with the Rocking.

Positional

Release

A horse with tight Serratus muscles usually has the lower part of its

neck braced on both sides. You’ll see

this as “lumps” on the sides of the neck where the Serratus attach to the

vertebrae. The two Positional Release techniques

that I’ll describe will release this tension.

Positional Release and Rocking should be done after the other neck

massage work.

Positional Release #1 – This

form of Positional Release is shown in photos in lesson 6. The horse will need the freedom to bring its

neck around toward its side, so it will need to be untied. As my example, I’ll describe Positional

Release on the left side.

Face the left side of the horse’s neck.

With your left hand on the halter, put your right hand (fingers or fist)

along the top edge of these lower neck vertebrae (C-4, 5 and 6; you can’t reach

7). Push the neck away from you as you

bring the horse’s head around toward you.

You will need to hold the horse’s head in place as you push the neck

away.

Be prepared to have to use a lot of pressure in pushing the neck

away. Use some deep pushing pressure

with thumb or fist and some short stroke friction to get this portion of the

neck to yield.

The aim is to release the tension where the Serratus attach to the

vertebrae. You’ll be pushing the neck

away from you, out to the right, causing the right side to stretch around to

the left. When this stretch occurs, the

head will come around toward the horse’s left shoulder or ribs without you having

to hold it there. This releases the

tightness on both sides. The left side

(because of the massage work) has gained the capacity to contract and the right

side lengthens. Repeat on the other

side. Try to get the horse to hold this

position for 5-10 seconds.

Sometimes the horse will start circling, just go with it and keep the

pressure on. The circling helps the

release.

Positional Release #2 – This

is essentially the opposite of Positional Release #1 in that the horse will

bend its neck away from you. I did not

show photos of this in lesson 6.

For this, again (as my example) you’ll stand on the left side of the

horse, facing the left shoulder. You are

going to reach under the neck with one of your hands; you can use either hand

to do this, whichever is most comfortable for you. If you reach under the neck with your right

hand, your left hand will be on the horse’s halter, but instead of pulling the

head toward you it will be there to encourage the head to go to the right as

the neck begins to bend to the right. If

you use your left hand to reach under, use your right hand to stabilize the

withers and keep the horse from moving.

Now, with the one hand, reach under the neck and “dig in” with you

fingers on the upper edge of C-4, 5 and 6.

Pull toward you; you’ll probably have to use a lot of pressure. The horse should arch its neck around to the

right, bringing its nose around to its shoulder or ribs. Try to get the horse to hold the position for

5-10 seconds. Occasionally, the horse

will stretch the neck down to the right, rather than around. It’s not quite as good a stretch, but it may

be the best the horse can give. Do this

exercise from both sides.

This technique requires a lot of finger strength, but there are a couple

of reasons for doing it. First, because

the horse’s neck is bending away from you, it will be able to stretch around in

a long smooth arc without your body being in the way.

Second, since the neck vertebrae have only muscles and ligaments (no

bones) for support, it is very easy for the vertebrae to be pulled out of

alignment. This misalignment usually

requires a chiropractic adjustment; but occasionally the misalignment may only

be slight and caused by an uneven tension between muscles that hold the

vertebrae in place. This particular

technique will sometimes release that tension and you will feel and hear the

vertebrae settle back into place. It’s not

something you are trying to do—we DO NOT do chiropractic adjustments—but it

does happen sometimes. So, if you hear

this “pop”, don’t worry that you’ve done something wrong. Usually the horse will tell you it was a good

thing by chewing and giving a big sigh.

If the misalignment is in the vertebrae themselves, not caused by muscle

imbalances, this technique will not correct it.

Rocking

Rocking is a technique that can be used effectively to break up tension

and bracing between the different parts of the horse’s body and can be used at

any time during a massage. Because the

neck is “hanging out in space”, rocking can be quite effective at loosening

neck tension. It is particularly

effective at loosening the joint between the last neck vertebra and the first

vertebra of the rib cage. It also makes

a nice finishing touch at the end of a massage.

Below are two different forms of rocking that I use often on the neck.

Rocking #1 – Stand near the head of the horse, facing the neck. Place a hand on either side of the lower neck

where you see the neck braced; usually this will be where the neck joins the

shoulder or over the “lumps” of the 3rd and 4th

vertebrae. Push the neck back and forth

with your hands, setting up a nice smooth rhythm that gets the whole neck

rocking.

Rocking #2 – This form of

rocking moves the base of the neck in relationship to the shoulder portion of

the rib cage. It’s meant to loosen the

junction between the last neck vertebra (C-7) and the first thoracic, or rib,

vertebra (T-1). Restriction at this

joint does not allow independent movement between the neck and rib cage and

inhibits bending and lateral flexion of the neck.

My example is from the left side of the horse, but because this

sometimes works better from one side than the other, do it from both

sides. Stand on the left side of the

horse, facing the shoulder. Hold the underside of the neck, somewhere in the

lower half, with your left hand. Lay

your right forearm diagonally across the left side of the horse’s rib cage, grasping

the withers with your right hand. You

want to set up a rocking motion between the lower neck and the withers by

pushing and pulling between these two points.

If the withers don’t move, use your forearm to move the rib cage. Occasionally, with very stiff horses, I’ve

used elbow pressure in the space between the ribs to get the rocking

started.