Equine Massage

LESSON SEVEN

I. Safety

II. Body

Mechanics

III. Massaging

the Horse

I. SAFETY

Safety for you, the horse, other people and animals in the vicinity has

to be your first priority. You do not

want to be responsible for injury to the horse you’ll be massaging or to

others. It is your responsibility to be

award of your surroundings.

SAFETY FOR THE

HORSE

First you have to decide how to restrain the horse. You need to know if it ties RELIABLY. If so, does it do so just on a single rope or

in cross-ties as well? If the horse does

not tie reliably it will need to be held by someone.

Next, you need to decide where to tie the horse. You do not want to tie to a tree or a free

standing pole. The horse is going to move

during the massage and you don’t want it circling a tree or pole, winding

itself up short. The best place is the

corner of a stall where it can only move 90 degrees. The outside of a stall or a fence line where

it can move 180 degrees will also work.

Cross-ties work well as long as the aisle is not too wide and the

cross-ties are not attached too high on the walls. If either of these is the

case, the horse could turn around in the cross-ties and this can be

dangerous. Wherever you tie the horse,

try to position it in such a way that it can see what’s going on.

Try to keep distractions to a minimum.

A distracted horse can be difficult.

Dogs and young children are particularly distracting. But one of the biggest distractions will be

flies and other insects. I ask owners to

spray the horse.

If you object to working on a horse that has been

sprayed with insect repellent, you might bring some of your own that you’re

comfortable with. But if you do,

be sure to get the owner’s permission to use it—some horses are very sensitive

to different kinds of sprays.

Because it is important for the horse to be aware of the changes

occurring in its body during the massage, I don’t let the horse eat hay or

other foods while I’m working on it; this can be a major distraction. However, on some few occasions, I have worked

on horses that were so hyper-sensitive about their bodies they seemed ready to

climb out of their skins. In these

cases, I agreed to allow them hay to divert their attention away from their

bodies in their first massage session.

The horse is going to move around during the massage, this is part of

the process. Move buckets, tack

trunks, stools, etc. out of any areas where the horse might move. Keep dogs, cats and other animals away. If the horse is standing in the barn aisle,

make sure that other horses can’t reach out and annoy it.

My preference when working on a horse is to use a regular leather or

nylon halter rather than a rope halter.

I like the stability they offer, especially when I’m working on the neck

and head.

Because horses will move around during their massage, they will

occasionally step on one front foot with the other. Over the years, I have had two horses pull a

shoe during a massage. If a horse has

front shoes or long, built-up feet and you’re concerned about this, you might

ask the owner to put bell boots on them.

Even with an apparently good natured horse, someone who knows the horse

well should be there during the first sessions.

In addition to the safety factor, they can often give odd pieces of

information that will have a bearing on the horse’s problems. Later, when you and the horse are comfortable

together, you can work without someone in attendance, but there should always

be someone close by.

DO NOT WORK ALONE WITH STRANGE HORSES.

Any tools or equipment you use should be clean and disinfected. In addition to the tools that I use on the

horse, I also carry with me a leather muzzle, bell boots, longe

line, longe whip and insect repellent (for people and

horses). All of this is equipment that

you might have a need for and can’t be sure it will be available.

Be aware of the surface the horse will be standing on. Try to avoid slick surfaces where the horse

might slip—rubber mats, dirt or shaving are the safest.

SAFETY FOR

OTHER PEOPLE

1. Ask that other animals (horses, dogs,

cats, etc.) be kept away. If they make

the horse nervous, it could kick or react in some way.

2. Be sure that other people are not where

they could get stepped on or kicked as the horse moves around. Also, other people standing close to you and

the horse could interfere with your ability to move freely and cause you to get

stepped on or hurt.

3. Horses are sensitive to the emotions of

the people around them. Some owners will

fuss, touch and worry over their horses as you’re doing the massage. Explain that it’s difficult for a horse to

divide its attention between two people touching it at the same time. Ask the owner to sit somewhere away from the

horse unless you need their help.

II. BODY MECHANICS

Though the intent of

massage is to relieve soreness and tightness in the muscle

structure, in order for it to be effective at doing so on a permanent basis

(not just temporary relief) the pressure will often be uncomfortable before it

feels better, especially when you’re applying pressure to areas that are

already sore. Horses will use a wide

range of body language to tell the person doing the massage how it is feeling

about the area they’re working in, the touch and the pressure.

The first signs of discomfort may be as subtle as the twitch of an ear

or a turn of the head. The horse might

pick up a foot and threaten to kick. The

more sensitive you are to these little signs, the less the horse will feel the

need to over-react in order to call attention to its discomfort. Being aware of

the little signs allows you to adjust to the horse’s tolerance level before it

starts to over-react.

Though the greater majority of

horses that you work with will give you very little difficulty, remember that

many of these horses are hurting and can be defensive. Some of them will try to kick and bite.

With all of the above in mind, how you use your body when doing massage

becomes very important for your safety.

Also, your body mechanics can be the cause of stresses and strains that

affect your health and soundness; this is particularly true of your hands.

In human massage schools, students are taught how to keep their bodies

sound and functioning properly as they massage other people. In massaging horses, this is just as

important, and there are some aspects of your body mechanics that I want to

bring to your attention. They are:

1. Using your hands

2.

Using your body weight

3.

Placement of your feet

Care of your hands is very important; it is one of the reasons why I use

some grooming tools in my work. They give

me greater leverage and depth when I need it without putting undue strain on my

hands. Using the heel of your hand, your

fist or elbow whenever possible will also help preserve your fingers,

particularly your thumbs.

A regular routine of stretching your hands can help relieve strain; but

even better would be regular maintenance massage for yourself, with extra

emphasis on your hands.

During a massage I usually have two hands on the horse at all

times. Even if only one hand is doing

work, the other will be giving me information about reactions in the horse’s

body. It gives me a contact point to

feel the horse’s movement, where it’s going and what it’s going to do. If you have this contact point and the horse

moves toward you, it will push you with it instead of running over the top of

you. The contact between the two of you

is like ballroom dancing—you move together because you’re connected.

If I’m using both hands to do the body work, I will often lean my head

or shoulder against the horse’s body to get that same information and contact

point. This is especially true when

working on the chest and upper legs.

Using your body weight to support your hands and arms is another way to

increase your effectiveness and relieve the hands and arms of much strain. Put you body weight behind your pressure,

leaning either from your feet of hip joints.

Your force should go up through your legs, hip joints and torso and,

finally, through your arms and hands.

Your body weight should support your arms. If you’re muscular and somewhat tall, it’s

easy to fall into the habit of just using your arms, pushing just from your

shoulders. But it’s better for your body

if you stand with your feet away from the horse and lean your weight behind your

arms. It’s also safer for your feet.

When you’re doing massage on a horse, you’re usually going to be much

closer contact with it than under normal circumstances like grooming and

tacking-up; it’s easier to get stepped on.

Horses step where they lean their weight. When a horse leans its body in a direction,

it will then move a foot in that direction to catch its balance—the feet go

where they need to be in order to support the body. So, even though your hands on the horse’s

body will usually give you warning that the horse is going to move, it’s also a

good idea to keep your eyes on their feet.

Their body will tell you they’re going to move, but it won’t necessarily

tell you where they’re going to put their feet.

If you use your peripheral vision you can see all four feet at the same

time and still see where you’re working.

Keep your feet separated, with one foot behind the other as much as

possible. Keep most of your weight on

the foot farthest from the horse. This

allows you to move your other foot quickly and easily if the horse steps toward

you. If you’re standing in front of a

horse, stand with your feet wide apart in case the horse steps forward. Wear sturdy shoes, but I don’t recommend

steel-toed shoes.

A horse that is hurting or sore may try to kick when touched. Most horses will just threaten and, through

your hands, you can usually feel it coming.

I will feel it just as the leg start to move and I’ve found that a light

slap on the horse’s back with the flat of my hand (one

that makes a noise) will usually defuse the kick.

If a horse is inclined to kick, it will usually do so when you’re

working on the belly, groin or stifle.

If the horse is really touchy about these areas, you may decide to leave

them for another session, after the horse is more comfortable with what you’re

doing. If a horse indicates it does not

want me to work in that area in the first session, they will usually let me do

so in the second session, but, with a few horses, I have had to wait for the

third session.

When working around the stifle and groin, I will often have my forearm

or hand resting in front of the stifle or just above it. If I feel the horse start to lift the leg I

can put downward pressure on the stifle and stop the kick.

Horses that really intend to kick don’t usually give a lot of warning;

they don’t threaten. The kick seems to

come out of nowhere. But these horses

usually do tell you to watch out way in advance. With these horses, you’ll know almost

immediately, when you first meet them, that they are going to be

difficult—their body language will give you fair warning.

Horses that try to bite are another problem you may encounter. This will usually happen when you’re working on

horses with sore shoulders and necks.

Normally, I’ll just deflect the attempt by reaching up and gently

touching their face, or push their face away.

If they get a little more aggressive, I’ll put my elbow up and let them

run into it or have the owner hold the head.

But if the horse is very persistent it can get to be a distraction to

the body work. I worked on young

thoroughbred race horses for four years and used a leather muzzle on many of

them. In that way they could bring their

heads around and “talk to me” and I didn’t have to worry or react. I still carry one in my box and do have a

need for it occasionally.

Horses that strike can be dangerous, but they’re rare, and are usually

stallions. In the four years of working

on the young race horses only two ever tried to strike, and they were both

incredibly sore in their shoulders. Be

very careful when working on horses that want to strike; or you may choose not

to work on them.

On a few rare occasions, I have agreed to work on horses that have been

sedated. It’s not an ideal situation,

but the horses needed help and it made it safe for me (these were usually race

horses). Horses that might strike could

fall in this category.

There are other safety factors that will come up when massaging the

different areas of a horse’s body, but I’ll discuss them when describing the

work on those areas.

SUMMARY OF YOUR

BODY USE

1. Support your arms and hands with your

body weight.

2. Keep two hands on the horse—one gives

information while the other works.

3. Be aware of where your feet are and how

you can move them quickly.

4. Know how to deal with horses that kick

5. Know how to deal with horses that bite

6. Know how to deal with horses that

strike

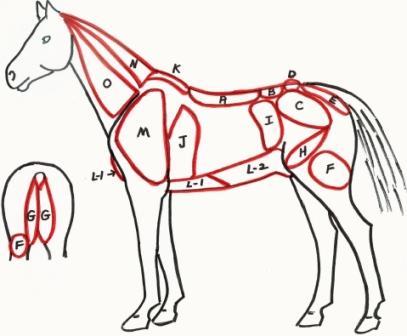

III. MASSAGING THE HORSE

This section will take you through a full body massage. There are several diagrams that go with this

lesson. They show the horse’s body

divided into various areas. These areas

are labeled and there is an accompanying description that describes the following:

1.

the important muscles in these various areas

2.

what these muscles do

3.

massage techniques that are the most effective for the

area

4.

other pertinent information applicable to the area

I focus on areas of the body rather than on specific individual muscles

because your massage will rarely affect just one muscle. Muscles occur in layers and overlap one

another. Some muscles are very thin, so

it is easy to be affecting deeper muscles as well as the more superficial ones.

With each area I will refer you to pages and diagrams in two anatomy

books that were on the recommended list for this course. In this way you will be able to see the

various layers of muscles, how they overlay one another and interact. This is also a way to get a good review of

the skeletal and muscular anatomy from lesson two.

I will give you reference pages in Peter Goody’s “Horse Anatomy” and

“Horse Anatomy—A Coloring Atlas”. If you

have other anatomy books, use them as well.

All anatomy books will have slightly different ways of showing the same

muscles and structures.

Cross-referencing among them will give a more complete picture.

I will be describing a progression from one area to another for a full

body massage that starts with the horse’s back, goes into the hindquarters,

works forward through the belly line into the shoulders and neck and finally

finishes with work on the poll, head and jaw.

This is a good progression if you’re doing a full body massage for

relaxation or maintenance. If you’re

massaging a horse that has specific problems, you will not necessarily follow

that progression. After having taken a

history of the horse and made an evaluation of its structure and movement, you

will have a sense of where the most obvious problem is. After loosening up the back, you will proceed

to that area.

I know that many people start their massage with the head and work back

toward the hindquarters. My

understanding of their reason for doing so is that there are powerful endorphin

points in the head that induce the horse to relax quickly and helps make them

more accepting of the rest of the massage. Because structural massage and body

balancing are addressing soreness and balance on a much deeper level than other

types of massage, including sports massage, it often involves using pressure

that can initially be uncomfortable enough to disrupt any relaxation gained by

starting with the endorphin points in the head.

PRESSURE IN

YOUR MASSAGE

How much pressure do you use?

All massage requires pressure; how much pressure depends upon the type

of massage. You always have to get a

response from the muscle.

In relaxation massage, the response you want will only affect

superficial muscle tension. Your

pressure would be smooth and gliding; it should not cause discomfort and a horse’s

responses will be to relax, sigh, soften the eyes and chew.

Other kinds of massage will need more pressure in order to be

successful. These other types of massage

will be working on muscles at a deeper level and dealing with muscles that may

be tight and sore from injuries, chronic stress and over-use. In order to relieve this soreness and

tightness, the pressure will need to be enough reach the deeper muscles,

separate the bound-up muscle fibers and reset the tension in the neurological

component of the muscles.

How do you know if you’re using enough pressure, too much pressure or

too little?

Effective pressure (the right amount) has to make a change in a

muscle. The change we’re looking for is

that the muscle yields to the pressure you’re using. When the horse yields, it will do so by

moving away from that pressure. With

extremely tight muscles, you will have to use a lot of pressure. If the horse is very sore, it will only take

a small amount of pressure to cause the horse to yield and move. In both cases, if the horse yields to the

pressure, it was effective pressure whether you had to use a lot or only very

little. At first the horse will make big

movements. As soreness and tightness

diminish, the “away” movement will simply be the muscles softening and yielding

to your touch.

If a horse is very sore, and you continue to push even as the horse is

flinching and moving away, you’ve held the pressure too long. The most effective pressure for very sore

horses is “press and release”. As soon

as the horse gives a response, you release the pressure. You keep repeating this press/release

sequence, moving over the sore area until the horse’s responses become quiet

releases and yields to your finger tips.

Muscle density plays a large part in how much pressure you need to use

in your massage. Horses with heavy,

dense muscles will require a lot more pressure than lighter muscled horses such

as Arabs or Thoroughbreds. In a heavy

muscled, tight horse, if you get no response to your pressure, then the

pressure is not enough and is, therefore, ineffective.

In human massage, effective pressure is often described as being “a good

hurt”. Horse’s bodies seem to also

understand this concept. Experiment with

pressure; don’t be afraid of hurting the horse—it will tell you if you’ve gone

too far; and all you have to do is release the pressure and the discomfort is

gone. But you’ll never know how far to

go if you don’t experiment.

THE MASSAGE

I start my massage with the long back muscles. The back is the connection between the

forehand and hindquarters and it is going to be affected by tension and

imbalances from both areas. I will

loosen the back first, relieving any soreness and tension there before going to

the area where I saw the major problem.

With the deep structural work, relieving the soreness in the body of the

horse (especially the back) is just as effective at achieving mental relaxation

as doing the endorphin points in the head first. Also, many of a horse’s problems actually

originate in the back because of rider imbalances and bad saddle fit.

A. LONG BACK MUSCLES

1.

Peter Goody – Horse Anatomy – diagram 3 (pg. 17), diagram 4 (pg. 21),

diagram 5 (pg. 25)

2.

Horse Anatomy – A Coloring Atlas, plates 16 and 17

The major muscles of this area of the back are the Spinalis

dorsi, Longissimus dorsi, Iliocostalis dorsi and the thin fascia portion of the Latissimus dorsi. Palpate all three of the muscles to determine

if all are sore or just one or two.

Usually the sorest will be the one closest to the spine, the Spinalis dorsi.

Techniques

If these back muscles are TIGHT, but not sore, you will use techniques

that separate the muscles fibers in order that they can stretch more easily.

Tight muscles can be “cemented” together either by lymph fluid that has

pooled in a muscles or from scar tissue.

Appropriate techniques for these muscles if they are very tight (but not

sore) would be friction and muscle combing.

The most effective direction would be across the fibers. Circular friction also works well here.

As the muscles begin to loosen or if they were just moderately tight,

you can use a technique I call “press and glide”—a technique I use

frequently. I will use compression to

push down into a muscle and then, either with the heel of my hand, finger tips

or some type of “tool”, push through the muscle. You can use this technique going across the

muscle fibers, with the fibers or you can use a circular movement. You will work your way down the muscles by

pressing and then gliding a few inches, then repeat, working your way down the

muscles.

Tools that you could use would depend on the degree of tightness and

could be the stiff, serrated rubber curry comb, the plastic “bristle” type of

curry comb, some type of Grooma grooming tool or a

mane comb.

If these muscles are SORE, you will find that the best initial technique

will be one that uses a simple press-release approach. You would do simple compression using just

your finger tips, working up and down the back muscles. Go slowly and constantly explore how much

pressure you can use. Gradually, as the

soreness decreases, you can use some effleurage using either the heel of your

hand or finger tips. It would be very

unusual to use any tools on sore back muscles.

If you feel any obvious knots or hard spots in the muscles (chunks in

your peanut butter) do trigger point massage in those places.

One of my favorite approaches when working on sore backs is to stand on

one side of the horse, reach over the backbone and use my finger tips to first

push down into the muscle closest to the vertebrae, then pull towards the

backbone (toward me). I work my way down

the muscle, moving an inch at a time (this does not work well with long finger

nails).

If, as you start your massage with the long back muscles, they do not

seem particularly tight or sore, use either slow effleurage or friction in a

circular motion and work your way down the muscles from withers to croup

bone. You will do this as a general

loosening before going on to the problem areas.

B. LOINS

1.

Peter Goody – diagram 3 (page 17) and diagram 4 (page 21)

2.

A Coloring Atlas – plates 16, 17, 6

The lumbar area (loins) extends from the last thoracic vertebra to the

croup bone. This is the low back in the

human body. Remember that the last

thoracic vertebra is way up underneath the saddle and the last rib arcs back

from there; there is a lot more loin muscle than you may think.

The superficial muscles of this area are the same ones that I described

in section A – the long back muscles, but I have divided the area into two

sections because the feel in the muscles will be different here. In the loins there are no bones supporting

the spine, only muscles, so the muscles have to be stronger.

There is a heavy, dense muscle under the long back muscles that is the

major support for the lumbar vertebrae.

This is the Quadratus lumborum. It is very deep and is not shown on most

equine anatomy charts. To get an idea of

its structure and placement, look it up in your human anatomy book.

Because of the strength and density of the Quadratus

lumborum, it gives a different feel to the muscles in

the loins. Expect them to feel heavier,

tighter and more dense. Also, in this area, you can feel the outer

edge of the Iliocostalis. It will feel like a tight rope running

between the last rib and the point of the hip.

Techniques

If this area is not sore, but just TIGHT, brisk, cross-fiber friction is

a good technique to use. Also,

cross-fiber compression works well. This

technique is done more slowly that friction.

In this you would press down into the muscle, push across it, then

release. Repeat this, moving over the

loins. It is usually helpful to use some

kind of tool like the stiff rubber curry when working on the loins unless the

area is very sore.

If the area is SORE, use as much compression as the horse can handle,

moving slowly over the whole area.

“Press and glide” should work well, but if the muscles are very sore,

just use finger tip compression (without the glide).

Because of the density of the area, you may not feel the muscles of the

loins soften as much as muscles in other areas, but, as they begin to release

tension, the horse will start to shift its stance in response to your

pressure. As this happens, you will see

the hind feet begin to move to a more squared position. This will tell you that you have obtained

good releases. Also, the horse will

begin to lower its head, chew and its eyes will soften.

C. TOP OF HAUNCHES (gluteus muscles)

1. Peter Goody – diagram 4 (page 20), diagram 17

(page 55)

2. A Coloring Atlas – plates 16, 17, 33

There are three gluteus muscles in each side of the haunches, but only

two are where they can be massaged.

These are the middle gluteus and the superficial gluteus. For the purpose of massage, I will treat them

as one entity.

Some of the look of these muscles is going to be breed related (think

Quarter Horse and Thoroughbred), but a lot of their development and condition

is going to be the result of how a horse uses its body.

These two muscles have something of a “tear drop” shape and fill the

greater portion of the space on the top of the haunch, going from the edge of

the pelvic bone to the hip joint. These

muscles are, by nature, power muscles.

They control the movement of the pelvic bone. Their job is to support the pelvic bone,

allowing it to drop down when they lengthen and bring it back to its normal

position by contracting. Proper

lengthening and contracting of these muscles affects how well the hind legs

swing back and forth, so if these muscles are tight, they will restrict the

mobility of the hip joint.

Techniques

If these muscles are TIGHT, a combination of cross-fiber friction,

compression and muscle combing are effective.

The use of a stiff curry comb or mane comb works well on these muscles

and protects your hands.

These muscles can become extremely sore in a horse doing work that

requires a great deal of forward/backward thrust, such as racing and

jumping. They are subject to pain from

both stress points (at the origin) and trigger points (in the belly). Review the photos in lesson 6—they show both.

When these muscles are SORE, use the static pressure for stress points

and trigger points, but you can also use finger tip compression in a press/release

mode over the bulk of the muscles as well as connective tissue massage over the

gluteal fascia (Peter Goody – diagram 3, and A

Coloring Atlas – plate 16). As the

soreness begins to subside, you can start some effleurage in gliding motions.

A word of caution when working on sore gluteus muscles – the horse is

very likely to kick. They will usually

kick out behind, but can just as easily kick forward. Be careful.

When working on these muscles, it is more effective if you can work from

a position somewhat above and push down into the muscles; this is particularly

true if the muscles are tight rather than sore.

Unless you are quite tall, you may find that standing on some type of

stool or box will give you that height.

Tension and muscle tone in the gluteus muscles can be a significant

factor in the position of the pelvic bone.

The angle of a horse’s pelvis can vary greatly from a very flat position

(common in some Arabians) to a much steeper angle (seen in some Quarter Horses

and driving horses). If the glutes are short and tight, they will contribute to holding

the pelvis in a horizontal, flat position that inhibits the dropping of the

pelvis as the legs swing forward. Then, all of the leg movement and thrust has

to come from the hip joint; this puts a lot of stress on that joint.

A very steep angle to the pelvic bone indicates that the glutes are being held in an extended position by their

agonist muscles in the groin area. This

strong pull on the glutes will inhibit mobility of

the hip joint. You will see the problem

as an over-extension of the gluteal muscles, but the

real problem is elsewhere. You will do

massage that separates the muscles fibers of the glutes

and prepare them for better contraction, but the solution will involve

releasing tension in the muscles of the groin.

D. CROUP BONE AREA

1. Peter Goody – diagram 17 (page

55) and diagram 22 (page 55)

What we call the “croup bone” is actually the point where the two sides

of the pelvic bone come together in the back.

(This is called the tuber sacral.)

The lumbar/sacral joint of the horse is under this junction of the

pelvic bone. (Review the important

aspects of this joint from lesson two.)

In the human pelvis, the sacrum is held in place by the two sides of the

pelvic bone, rather than being under it.

My thought about the difference in the placement of the lumbar/sacral

joint of the horse would be that the horse needs a much greater range of motion

in this joint and this placement allows that.

When there is tightness or soreness in the gluteus muscles, the

attachments around the “croup bone” will also be affected and there will be

interference with the working of the lumbar/sacral joint beneath it.

As part of loosening the haunch muscles, you will also want to work

specifically all around the croup bone.

Techniques

Use direct finger pressure that pushes down into the muscles all around

this bony area. You could also use

friction. The amount of pressure you use

will depend on whether the area is tight or sore.

If the horse has a steep croup angle, the haunches may flatten a little

as the muscles release—this is good.

If the horse has a steep croup angle and, in addition, the croup bone is

very prominent (goose rumped), and the muscles around

it do not seem to release well to your massage work, it is possible that there

is a problem with the lumbar/sacral joint in which the sacrum has been pushed

upward against the last lumbar vertebra.

This could very possibly indicate a chiropractic problem.

E. UPPER HAMSTRING ATTACHMENTS

1.

Peter Goody – diagram 3 (page 17), diagram 17 (page 55), diagram 22 (page 65)

2.

A Coloring Atlas – plates 16, 17, 33

The term “hamstrings” refers to three

muscles that run down the back of the leg from the sacrum to the lower portion

of the haunch. They are the Biceps femoris, Semitendinosus and the Semimembranosus. These hamstrings and the quadriceps (quads)

are the prime movers of the horse’s hind legs.

The quads pull the leg forward and the hamstrings pull the leg backward.

As was shown in lesson 2 (Anatomy), the horse’s hamstrings go all the

way up to the sacrum for their upper attachments rather than ending at the ischial tuberosity (seat bone) as

ours do. The Biceps femoris

and the Semitendinosus attach to the sacrum in the

area between the croup bone and the tail.

The upper attachment of the Semibembranosus is

under the tail. Be careful working this

attachment.

As the leg is brought forward by the quads and the Tensor fascia latae, the hamstrings are lengthened by the pull of those

muscles and this stretching of the hamstrings starts from all the way up along

the sides of the sacrum. Their contraction

pulls the hind leg out behind the horse.

These upper hamstring attachments are extremely important. If they are tight, either in a short,

contracted state or in a long, extended state, they limit the forward swing of

the hind legs. The massage work in this

area goes in concert with sections C and D (top of the haunches and the croup

bone).

If the horse’s croup is flat, tightness in these upper attachments is

part of the problem and will usually be associated with short, tight gluteals. The

loosening that you’ll get with your massage will let these attachments stretch

and will be an important part of allowing the pelvis to drop into a more normal

position.

If the croup has a steep angle, these muscles will be over-stretched,

tight in the extended state rather than contracted. They will need to be worked on as part of the

over-all release of the hindquarters.

Techniques

If these hamstring attachments to the sacrum are TIGHT, but not sore, do

spot compression using thumb and finger pressure in a direct push into the

muscle attachments along the edge of the sacrum from the croup bone to the

tail. Cross-fiber friction (with fingers

or rubber curry) along the edge of the sacrum is another good technique. If the attachments are very tight, try some

muscle combing along the edge.

If the horse is SORE in the gluteus muscles, then the hamstring

attachments along the edge of the sacrum are very likely to also be sore. If this is the case, your work along the edge

of the sacrum will need to be lighter.

Try some light muscle combing with your finger tips, also do some thumb

and finger compression; just don’t work as deep as you would on tight

attachments. When working on the Semimembranosus attachment under the tail, stand well to

the side of the horse as you reach under the tail. I usually reach under to the attachment on

the other side since horses will usually react where they feel the pressure. That way, if they’re going to kick, it will

usually be with the leg on the other side from where I’m standing.

F. LOWER HAMSTRING ATTACHMENTS

1.

Peter Goody – diagram 3 (page 17), diagram 22 (page 65)

2.

A Coloring Atlas – plates 16, 17, 33, 34

Tightness in the lower attachments, just as in the upper ones, will

prevent a good forward/back stride in the hind legs, and tightness throughout

the entire length of these muscles will produce more of an up/down movement and

shorter strides.

In some horses these muscles are naturally heavily developed and this is

not necessarily a problem if the up/down motion is what a rider wants (Western

pleasure), but you still want mobility in the hip joint so that the jog is

fluid and smooth rather than tight and stilted. Tightness in these muscles is a major

problem if the horse’s work requires a big forward/back swing (galloping

horses, jumpers).

The largest and most accessible of the lower hamstring attachments are

those of the Biceps femoris. They will look like three lumps on the side

of the lower part of the haunch, just behind the stifle joint.

In addition to restricting forward movement of the hind legs, tight

contracted lower attachments of the Biceps femoris

can also rotate the stifle outward, causing the hind leg to swing forward in a

sideways position. This is a serious

problem because it can interfere with the correct movement patterns of all

three gaits—walk, trot and canter.

The lower attachment of the Semitendinosus

will be visible at the center back of the haunch, just above the hock.

The Semimembranosus lower attachment will be

just to the inside of the Semitendinosus, more to the

inside of the leg.

Techniques

I rarely find these lower hamstring attachments sore, usually they are

TIGHT. Effective massage techniques for

the lower attachments of the Semitendinosus and Semimembranosus would be friction across the fibers, muscle

combing and compression. I particularly

like to use a small rubber curry on these areas.

The lower attachments of the Biceps femoris

are more fleshy than those of the other two. In addition to the above techniques, you

could also use kneading. Thought the

name of this muscles, Biceps femoris, implies two

attachments, there are actually three, make sure that you work on all of

them. Work across the three heads then

work up the sections of the muscle toward the hip joint. For this, you can use “compress and glide”.

It also benefits the Semitendinosus and Semimembranosus if you used some deep effleurage up and

down the length of these muscles. They

are normally under a lot of tension and this is a good way to separate muscle

fibers and relieve some of that tension.

G. ADDUCTORS (the insides of the hind

legs)

1.

Peter Goody – diagram 22, Gracilis (page 65)

2.

A Coloring Atlas – plate 34 (this is a very good picture that shows many of the

deeper adductors

Remember the description of agonist and antagonist muscles and how they

work together to move bones away from their normal position and then back to

that original position? The muscles I’ve

been describing up to this point have all had to do with moving the body parts

in a forward/back motion (longitudinal extension and flexion). They are called extensors and flexors. But there are other agonist/antagonist muscle

pairs that move bones sideways. They are

called abductors (move limbs away from the center line of the body) and

adductors (move limbs back toward the center line).

The horse’s adductors are a group of strong muscles on the insides of

the hind legs that hold the hind legs close to the body. They work with the abductors on the outside of

the leg to move the leg sideways. The

abductors move it away from the body, and then the adductors move it back

toward the body and under it. They are

very important for lateral movements.

The massage that you do on the muscles on the outside of the haunches

will facilitate the abduction action of those muscles, but the adductors will

have to be addressed on their own.

The Gracilis muscles is the most superficial

(closest to the skin) of the adductors and the one you will feel under your

fingers, but it is a thin muscle and your massage will also be affecting the

muscles under it.

Sometimes these adductors will be so tight that you will have difficulty

even getting your hand in between the hind legs; the use of your hands will be

restricted and tools are not appropriate.

Techniques

These muscles are usually TIGHT, rarely sore. I have found kneading to be the best

technique for loosening them. It’s quite

effective and will not irritate the sensitive skin of this area. As you knead, you can also lean your shoulder

against the haunch and do some rocking.

H. QUADRICEPS (Quads)

1. Peter Goody – diagram 4 (page 20),

diagram 7 (page 31)

2. A Coloring Atlas –

plates 17, 34

After a contraction of the hamstrings pulls the horse’s hind leg back,

it is the quadriceps (along with the Tensor fascia latae)

that brings the leg forward by pulling the stifle forward.

The quadriceps muscle group is composed of three vastus

muscles and the Rectus femoris, but only two of these

are accessible to us to massage. One is

on the outside of the haunch between the stifle and the hip joint (the lateral vastus). The other

is the medial vastus.

It is on the inside of the leg, going from the stifle up the inside of

the leg.

The area around the stifle, especially

on the inside, is a sensitive area. Even

if the horse is not particularly sore, it can be sensitive or even defensive in

this area. Keep this in mind as you

work. As much as possible,

stand next to the haunch, not out in front of the stifle. This is where I keep one hand or forearm on

the horse’s body, just above the stifle, so that I can feel any upward movement

of the leg and press down to defuse the kick and keep the leg down.

Techniques

Lateral Vastus: Around the stifle, use finger tips in a

kneading motion and some finger tip compression around the top of the

stifle. Then, using either

the heel of your hand or some type of stiff curry comb, work from the

stifle upward to the area around the hip joint.

I primarily use a heavy back-and-forth motion (friction) going with the

direction of the muscle fibers. You

could also use compression and deep effleurage, depending upon how tight the

muscle is. With any of these techniques,

if you can use enough pressure to feel the femur under the muscle, you can

separate the muscle fibers by pressing the muscle against the bone. Also, do friction pressure all around the hip

joint.

Medial Vastus:

This is not an easy area to work on.

Most horses are sensitive about pressure on the inside of the leg as

well as being worried about any pressure in the groin. If they are sore in this

area, they can become pretty defensive.

The skin in this area, like that between the hind legs, is soft and

sensitive. Tools are not

appropriate. I use mostly finger tip

compression that pushes up into the muscle mass. Once the horse accepts pressure in this area,

you can support the outside of the femur with your shoulder or torso and use

enough pressure to push this muscle against the bone for better muscle

separation. You can also do compression

using the back of your fist or do kneading with your finger tips. Again, try to stand next to the haunch, not

out in front, and reach around to the inside of the leg.

If the stifle rotates outward, balancing the tension between the lateral

and medial Vastus will be crucial in bringing the

stifle back to its correct anatomical position.

After working on both of these muscles, you can test the balance between

the two by rocking the joint between your hands. Rotating this joint back to its correct

position will also involve having loosened and prepared all of the other

muscles in the haunch to facilitate this rotation. Work on the muscles in the groin area will

also be involved.